Nebraska researchers are making progress in showing that forever doesn’t have to mean forever when it comes to harmful chemicals, said Nirupam Aich.

Aich, McNeel Associate Professor of civil and environmental engineering at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, won the 2024 Faculty Research and Creative Activity Slam Nov. 13. Chosen by a panel of judges representing the broader Lincoln community, he won a $1,000 prize to support his research.

The Slam is an annual event held in conjunction with the university’s Nebraska Research Days, in which researchers present their work in five-minute, engaging talks, this year around the theme “Why does the world need your research?”

Aich noted that industry began producing a class of fluorochemicals made from carbon and fluorine in the 1940s. Known as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS, these highly stable chemicals are resistant to heat, fire and water, and they have gone on to become staples in nonstick cookware, firefighting foams, shampoo, food packaging and more.

“Essentially, PFAS is everywhere and in everything,” Aich said.

The problem: these “forever chemicals” leach into the environment, where they don’t degrade naturally and make their way into humans, where they cause cancers, developmental issues in infants and reproductive issues in women.

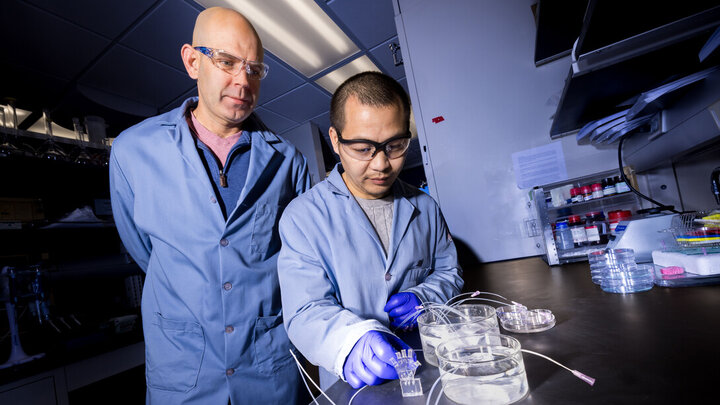

The Environmental Protection Agency has set regulatory limits for PFAS in drinking water, and Aich’s research team is developing new technologies to remove these compounds.

“We call this process ‘trap and zap,'” he said.

The process uses tiny nanoparticles to trap the PFAS molecules from water and then harness the power of sunlight to break them down. Basically, the nanoparticles pull the carbon and fluorine atoms apart and break their bonds, making them nontoxic and essentially breaking the forever cycle.

This is only the beginning, though. The EPA regulates only six PFAS compounds, and there are potentially more than 15,000, Aich said.

“We are hoping that with the advancement of AI and machine learning, we will be able to design nanoparticles for specific PFAS to trap and zap at lower cost and high efficiency," he said. "This will really create a future with safe water and food for all.”